Brand Monitoring: Defending Your Company Against Cybersquatting

Cybersquatting made headlines in recent weeks when Facebook filed a lawsuit against domain registrar OnlineNIC Inc. and its proxy service IDShield for cybersquatting and copyright infringement. The lawsuit concerned domain names that use the word “Facebook,” “Instagram,” or variations of Facebook’s brands with the intent to trick users into thinking that they are legitimate sites of the complainant.

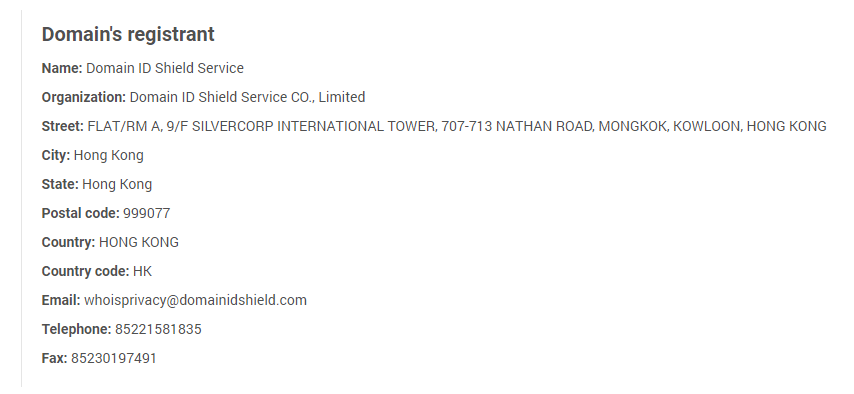

The domain names in question include www-facebook-login[.]com, facebook-mails[.]com, login-intstargram[.]com, and hackingfacebook[.]net. When we ran hackingfacebook[.]net on WHOIS API, the report stated that the registrar was indeed OnlineNIC Inc., which registered the domain in February 2010. However, the details of Domain ID Shield Service were the ones used as registrant information.

Domain ID Shield is a product of OnlineNIC Inc. that essentially replaces the registrant, as well as technical, and administrative details of the client with its own. So instead of taking legal action on individual registrants, which is difficult in this case, Facebook lashed out at OnlineNIC Inc. as it’s connected to complaints of domain abuse and for seemingly tolerating cybersquatting.

Facebook’s case is just one of the thousands of cybersquatting incidents that plague the Internet. And in this post, we explored what cybersquatting is, and how to detect it using tools such as Brand Monitor. We also examined some real-life cases of domain name fraud.

What Is Cybersquatting?

Cybersquatting or domain squatting is the practice of registering, using, and holding a domain name in bad faith. The domain names in question are usually related to brands and companies that are well-known and have a good reputation.

Threat actors may practice cybersquatting in the hope of reselling the domains at a high premium. They would spend less than a hundred dollars on a domain, for instance, and sell it for a much higher price when the trademark owner finds and decides to buy it.

Other cybersquatters intend to benefit from the popularity and reputation of the associated brand by selling counterfeit products. Additionally, cases where cybersquatters use the domains in phishing and other malicious activities are also on the rise.

Is Cybersquatting Illegal?

As early as 1999, the U.S. government signed into law the Anti-Cybersquatting Protection Act (ACPA), which aims to protect trademark rights holders from domain abuse. But, as cybersquatting is a global concern with bad actors located in different countries, jurisdiction has become an issue.

The American producer and actor Kevin Spacey Fowler, for example, fought to own the domain kevinspacey[.]com which was used by a Canadian resident. Interestingly, Spacey was advised by a judge in California to file the complaint in Canada instead, where there are no specific anti-cybersquatting laws.

To help solve the cybersquatting of trademarked names on a global level, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) commissioned the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) to create a report on the conflict between domain names and trademarks. The said report that came out in 1999 became the basis of the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), a standardized process for resolving domain name disputes that is still in use today.

As such, most instances of cybersquatting are illegal. What remains a significant problem, on the other hand, is that domain name registration has always been on a first-come, first-served basis, and practically anyone can register a domain name.

The Current State of Cybersquatting

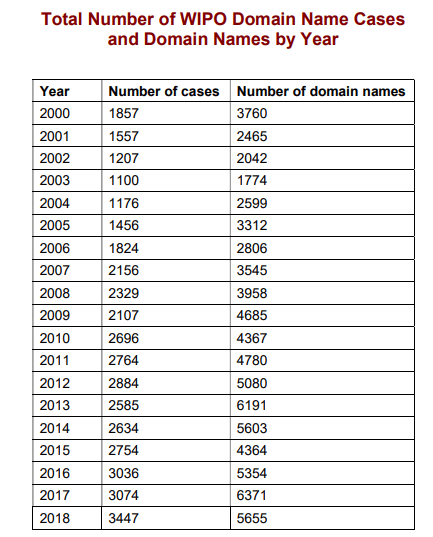

WIPO’s Arbitration and Mediation Center saw a record high of 3,447 UDRP cases covering a total of 5,655 domain names in 2018, a 12% increase compared with the previous year. According to WIPO’s press release published in March 2019, reported cybersquatting incidents have increased almost every year since 2000.

Source: WIPO Press Release Annex 1

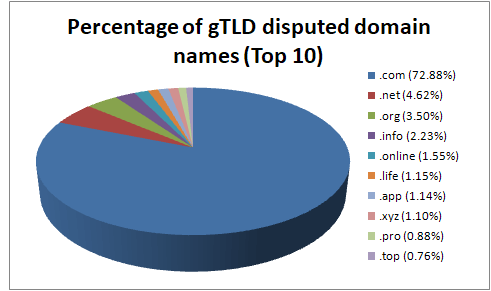

What’s more, legacy generic top-level domains (gTLDs) make up 87% of the total caseload, with .com leading at 72.88%. Other legacy gTLDs on the top 10 list of gTLDs with disputed domain names are .net, .org, .info, and .pro. The rest are new gTLDs such as .online, .life, .app, .xyz, and .top.

Source: WIPO Press Release Annex 2

Complaints received by WIPO come from various industries, with banking and finance topping the list at 12%, followed by Internet and IT and biotechnology and pharmaceuticals at 11%. The rest of the complaints came from different industries, including:

- Fashion (8%)

- Heavy industry and machinery (8%)

- Retail (7%)

- Entertainment (7%)

- Hotels and travel (5%)

- Food, beverages, and restaurants (5%)

- Electronics (5%)

- Automobile industry (4%)

- Media and publishing (3%)

- Transportation (2%)

- Insurance (2%)

- Sports (2%)

- Telecommunications (1%)

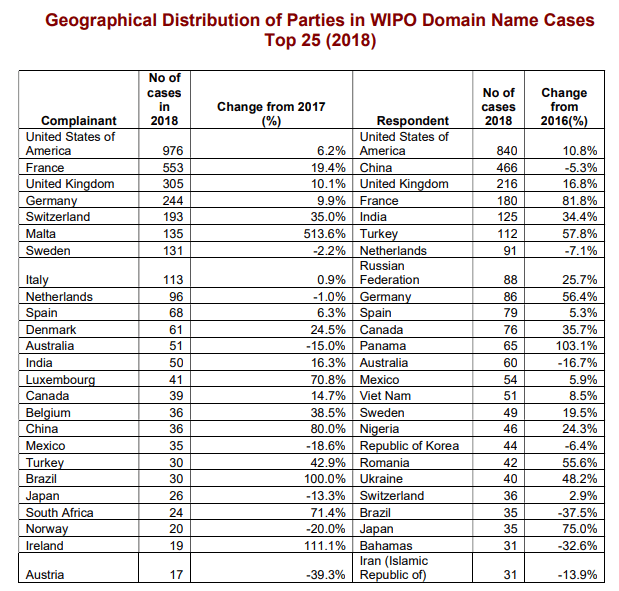

The majority of the complainants are from the U.S., followed by France, the U.K., Germany, and Switzerland. It’s noteworthy that most of the respondents were also from the U.S., with China coming in second, followed by the U.K., France, and India.

Source: WIPO Press Release Annex 3

All in all, cybersquatting is prevalent, and we see an upward trend in the number of related cases. While 2018 showed a record high, the coming years are likely to show even higher numbers — especially with the ICANN’s new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)-compliant policy of WHOIS data redaction.

There is, therefore, an urgent need for keen brand monitoring on the part of companies and trademark owners to detect any form of cybersquatting.

To quote WIPO Director General Francis Gurry:

“Domain names involving fraud and phishing or counterfeit goods pose the most obvious threats, but all forms of cybersquatting affect consumers. WIPO’s UDRP caseload reflects the continuing need for vigilance on the part of trademark owners around the world.”

Types of Cybersquatting and How to Go About Them

The first step in defending your company against cybersquatting is to recognize its different variations. Below are the most common types of cybersquatting and how you can detect them through brand monitoring best practices and tools.

Typosquatting

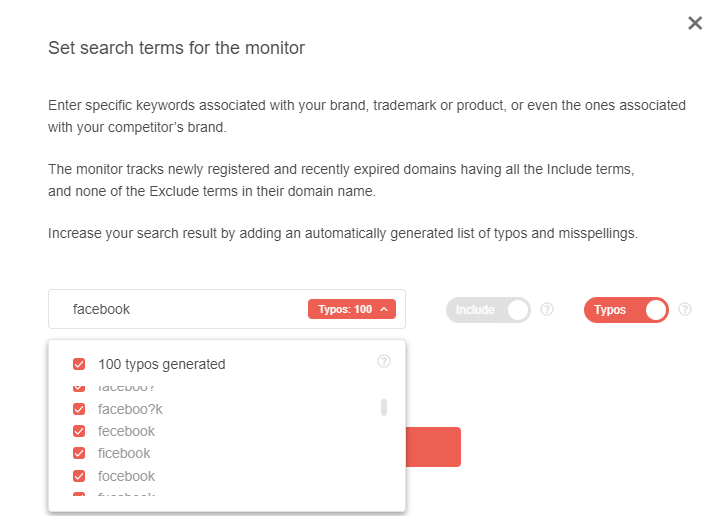

Typosquatting is a very common form of cybersquatting, and it only works because users frequently mistype or misspell domain names. As part of their fraudulent schemes, threat actors may use different methods, including misspelling a brand’s name (e.g., fucebook[.]com) or adding another word for a plausible subservice (e.g., facebookmails[.]com). When we ran “facebook” on Brand Monitor, for instance, 100 possible typos were detected:

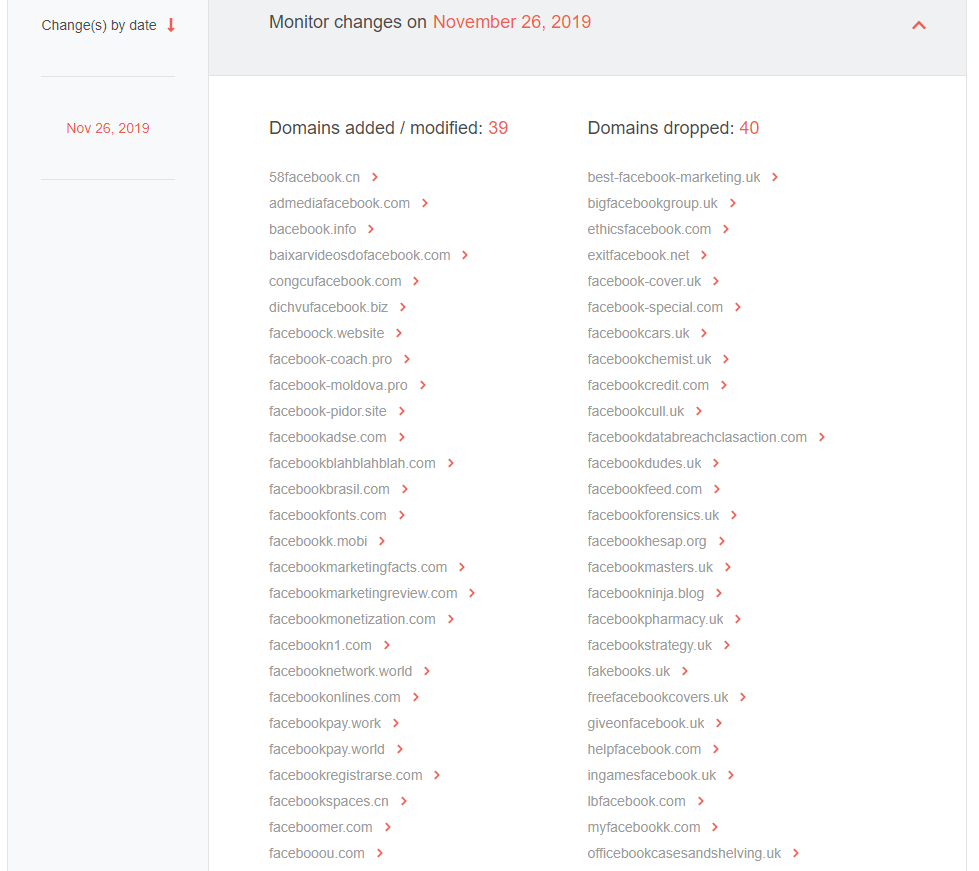

Within 24 hours of monitoring the Facebook brand, the tool returned dozens of domains added, modified, or dropped.

A quick investigation using WHOIS Search revealed that a majority of the domains added are not owned by Facebook, Inc., whose WHOIS data include a street address of 1601 Willow Rd, Menlo Park, California 94025.

Identity Defamation

Domain registrations expire, and cybersquatters can take advantage of that by purchasing expired domains if those are not renewed immediately. Such was the technique used by Wesley Perkins, a cybersquatter who bought thousands of expired domains by using fake names and offshore companies.

Perkins would buy recently expired domain names for less than £10 and later extort thousands of British pounds from the previous owners after redirecting the domain address to adult content. Telegraph exposed him in November 2017.

To avoid this type of cybersquatting, trademark owners must renew their domain registrations promptly. If you’re a well-established business, it may also be a good practice to renew old domains and redirect them to your new online property.

Infringement-Driven Cybersquatting

Infringement-driven cybersquatting is another form of cybersquatting that is commonly achieved by TLD swapping. The threat actor merely changes a TLD to a different one and is thus able to keep the whole brand name in the domain name in question. So instead of facebook.com, cybersquatters register domains such as facebook.xyz or facebook.top.

TLD swapping can also be detected by using Brand Monitor. For trademark owners, a good course of action might be to buy domains containing important brand terms across TLDs to avoid this form of cybersquatting — ideally before registering a trademark.

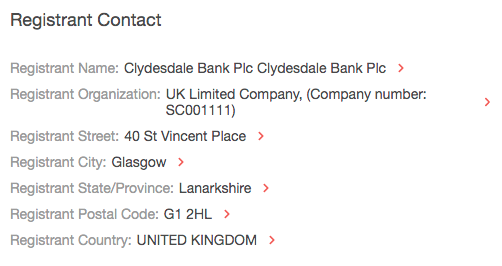

Take into consideration the case of Glasgow-based Clydesdale Bank, which looked into creating the domain name cybfx[.]co.uk after registering the trademark for “cybfx.” It found out too late that an individual named Eric Cheng from China had already bought the domain. Cheng demanded £95,000 in exchange for the domain name, prompting the bank to file a legal complaint. Clydesdale Bank eventually won and came to own the domain name.

We ran cybfx[.]co.uk on WHOIS History Search to confirm the change of domain ownership and found that from October 2017 to March 2018, the registrant details were as follows:

![We ran cybfx[.]co.uk on WHOIS History Search We ran cybfx[.]co.uk on WHOIS History Search](https://drs.whoisxmlapi.com/images/domain-monitoring-research/blog/brand-monitoring-defending-your-company-against-cybersquatting/image9-33.png)

On March 11, 2018, however, the registrant details changed to:

It would be better for Clydesdale Bank to register other domains in different TLDs too to avoid infringement-driven cybersquatting. That way, it can avoid potential damages to its reputation when cybersquatters use other cybfx domains for illicit activities.

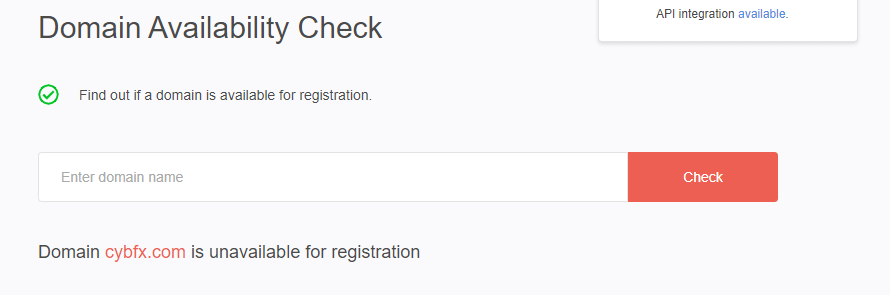

We checked the availability of cybfx.com using Domain Availability Check and found that it is no longer available.

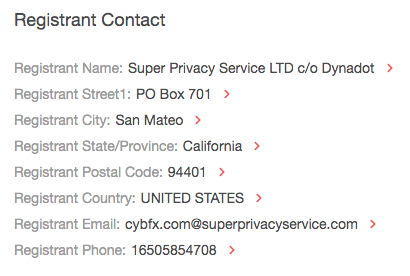

We thought that Clydesdale Bank may have already purchased the domain for safekeeping. We ran a WHOIS Search on cybfx.com but found that a different entity protected by the Super Privacy Service of Dynadot now owns it:

The domain is listed for sale by a private seller, and this could lead to at least three worst-case scenarios:

- The seller demands a massive amount of money if Clydesdale Bank decides to buy the domain.

- If the rightful trademark owner doesn’t buy it as soon as possible, a bad actor may purchase it and pretend to be Clydesdale Bank in phishing campaigns and other fraudulent activities.

- Clydesdale Bank may file a UDRP complaint and still spend a significant amount of money in legal fees.

Cybersquatting is a widespread problem for companies and trademark owners. It could cause monetary damage to an organization as well as posing risks of being associated with unreputable and even fraudulent activities.

In addition to filing UDRP cases against cybersquatters, however, companies must stay vigilant and proactive. Brand monitoring, powered by Brand Monitor, is one way to detect possible sources of cybersquatting, as well as tools that return reliable WHOIS data such as WHOIS Search, WHOIS History Search, and Domain Availability Check.